Physician Blog by Edward J. Bieber, MD

Rotator Cuff Disorders: The Facts

There is a great deal of information circulating about the rotator cuff and its disorders. Some of this is misinformation that has been printed in the lay press and unfortunately some of it has been disseminated by medical professionals either through a misunderstanding of current information or a desire to simplify the situation. This information sheet is meant to provide you with facts and where there are no facts, the best understanding that is currently available about these problems. I have relied on orthopaedic texts and information provided at the many courses that I have attended sponsored by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Over the past thirty years, I have treated several thousand patients with shoulder disorders and have extensive shoulder surgery experience including arthroscopic and open surgery. I regularly attend surgical and lecture courses provided by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons on shoulder topics and have endeavored in this pamphlet to share that information with you. I have excerpted some information from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, the Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.

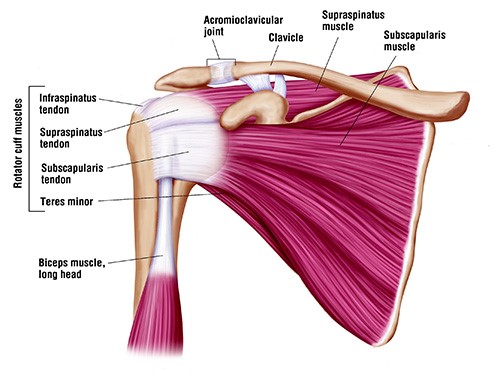

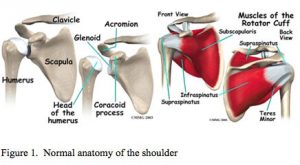

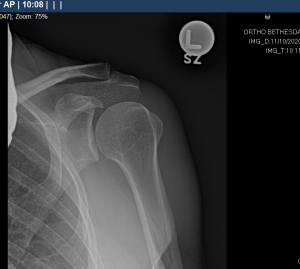

The rotator cuff is a group of 4 tendons (tendons are the connection of muscles to bone) that connect to the head of the humerus (the ball of the ball and socket joint of the shoulder). It is made up of the subscapularis, the supraspinatus, the infraspinatus and the teres minor. These muscles are responsible for many of the motions of the shoulder. The large muscle that is more superficial than these muscles is the deltoid muscle. The shoulder joint proper is made up of the head of the humerus and the glenoid which is the socket and is actually a part of the scapula or wing bone. The glenoid is circumferentially lined by a thick fibrous ligament called the labrum. The clavicle (collar bone) joins the roof of the shoulder, the acromium (which is also part of the scapula), to form the acromioclavicular (ac) joint.

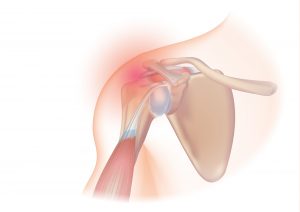

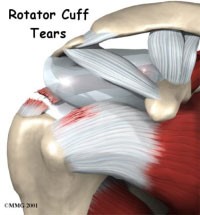

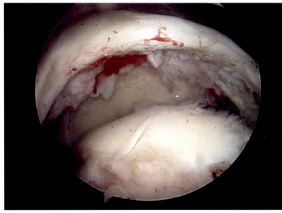

The rotator cuff muscles are relatively small and can be injured by an acute stress that exceeds their tolerance. Degeneration of the rotator cuff tendon also occurs from chronic use when the body’s rate of tissue damage exceeds the rate of repair. This is a normal part of the ‘maturing’ process. To conceptualize this process, think of a rope rubbing back and forth over a rock. It gradually becomes thinner (partial thickness tear) and eventually may tear all the way through (full thickness tear). The rotator cuff is a wide tendon so one may have a partial or full thickness tear through part of the tendon but not the entire tendon. In the population at large about 25% of people age 40-60 years old have partial thickness rotator cuff tears. By age 60, 20%+ of the population has a full thickness tear (all the way through a portion of the tendon) and by age 80 over half the population has a full thickness tear. There are many people with a full thickness tear that have minimal or no symptoms and don’t know they have a rotator cuff tear. As we age, the thickness, elasticity and quality of the tendon tissues deteriorate. The labrum also wears over time and a very large percentage of patients over 40 have some tearing of the labrum and most do not have any awareness of this phenomenon. There are secondary changes that occur in the shoulder concurrent with rotator cuff degeneration including bone spurs of the acromion and the ac joint. The obvious question is that if so many people have rotator cuff tears why do some have pain and dysfunction and others do not. This is not well established but there are many theories about this that have do to with the geometry of the tear, the basic anatomy of the individual and the stresses that are placed on the shoulder and the vascularity of the tendon. It is also why, even with a full thickness tear, sometimes the right treatment is not surgical repair but the presence of pain is often an indicator that in the long term surgical treatment will be more successful. Recent studies have clearly shown that patients with full thickness tears who chose surgery had better long term results in terms of function and pain relief than those who did not have a surgical repair. Also, most labral tears do not have to be treated surgically although there are some that require it.

The initial evaluation involves a history, physical exam and usually specific x-ray views to assess the bone pattern and integrity of the shoulder. The treatment will often involve rest, heat, oral anti-inflammatory (non-steroidals such as Advil and Aleve), cortisone injections in specific areas of the shoulder and eventually physical therapy. These treatments work gradually and require patience by the physician and the patient. Somewhere between 50-80% of patients even with full thickness tears can respond at least partially to non-operative treatment. There is no evidence to support the use of platelet rich plasma, human growth hormone or stem cells as a non-operative treatment for rotator cuff tears or as an adjunct to surgery for rotator cuff tears. There are some patients who do not respond to appropriate non-operative treatments and they require further evaluation.

The most commonly used test to evaluate the integrity of the rotator cuff is the MRI (magnetic resonance imaging). There is an assumption by the public that MRI testing is very exact and dependable. This is not always the case. MRIs like all tests are dependent on the quality of the MRI machine and the computer software that is used as well as the interpretive skills. In general, larger magnet and non-open MRI give superior images. Specific magnetic coils for certain body parts improve the imaging. Even given this, it is estimated that over half of partial thickness tears are not found on conventional MRI. Reports presented at the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons meetings indicate that MRI differentiates full from partial thickness tearing only part of the time. When needed, to improve accuracy, an MRI arthrogram (gadolinium is injected into the shoulder joint, not intravenous gadolinium) has significantly improved the accuracy of the test. The high false positive test rate with MRI without gadolinium injection may have led to many people having surgery for what is suspected to be a full thickness tear when they only had a partial thickness tear.

There are times when surgical intervention becomes the correct treatment. The concepts that are certain are that a full thickness tear cannot heal without surgery. A tear will become larger over time at a variable rate. And the larger the tear, the harder it is to repair and the lower the success rate. Therefore, if one is to proceed with surgery, it is far better to do the surgery sooner rather than later. It is also important to differentiate between an acute tear that is the result of a trauma and a degenerative tear that is one that has gradually occurred over time. As a rule, there is more urgency to repair an acute tear since it is a sudden loss of integrity and that the tendon is not worn and is very amenable to repair. A chronic tear provides a less urgent situation and offers more of an opportunity to try non-operative treatments. The younger the individual with a tear, generally it is more important to consider surgical repair because of greater demands that will be placed on the shoulder and the higher the likelihood of success because of tendon quality.

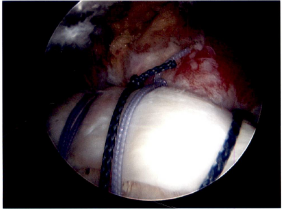

There are a number of different procedures based on the pathology. Generally, with partial thickness tears that have not responded to non-operative treatment the choice is arthroscopic surgery with debridement (shaving of the frayed tissue) of the rotator cuff often combined with removing bone spurs on the underside of the acromium. If there is significant arthritis in the ac joint that is symptomatic, a short section of the end of the clavicle may be removed at the same time. When a patient has a full thickness tear, the options are arthroscopic or mini-open rotator cuff repair. There is still debate about which procedure is more effective. In general, the quality of the open repair when tunnels are made in the bone (interosseous tunnels) has been felt to be stronger earlier in the healing process. Arthroscopic repair is dependent on inserting anchors in the bone to which sutures are attached. New arthroscopic devices and suture anchors, combined with a double row of anchors technique, have improved the quality of the repair. The only time an open repair is indicated is when bone tunnels are planned but if one is going to use anchors with an open incision, there is more trauma to the tissues than arthroscopic repair and overwhelmingly shoulder surgeons would not employ that technique. Post-operative sling immobilization and physical therapy rehabilitation is an integral part of the recovery to allow the tendon to heal to the bone. In the long run the repairs seem to have equivalent results with success of repair and range of motion. The advantage of the arthroscopic repair is the use of smaller incisions, decreased invasiveness (no muscles split) and the presumed decreased stiffness in the early postoperative phase. It is however important to note that some of rotator cuff repairs have some retearing of the tendon within one year of surgery, most without any symptoms because only a small portion of the repair retears. There is no correlation between the integrity of the repair and the resolution of patient symptoms. There are some rotator cuff tendons that cannot be repaired because the muscles have atrophied too much or the tendons have retracted or fibrosed and cannot physically be repaired. There is also the chronic situation where the lack of rotator cuff function has led to a severe type of arthritis called rotator cuff arthropathy which is amenable to a specific type of shoulder joint replacement.

This is meant to be a general overview and not an exhaustive discussion of rotator cuff pathology. I hope that it makes the issues clear and that I have corrected some misconceptions and given a candid view of what we know and what still needs to be worked on. I will be more than happy to discuss any of this information with you.

– Edward Bieber, M.D.

Dr. Edward Bieber of OrthoBethesda is the area’s most experienced total shoulder surgeon.

He has been performing anatomic total shoulders since 1986 and reverse total shoulders since 2007. He employs an integrated program of state of the art surgery with the OrthoBethesda physical therapy team to achieve superior results with both types of shoulder replacements. He has extensive experience with computer assisted directional devices and custom made devices for patients with significant bone deformity. Read more here and make an appointment with Dr. Bieber today.

Related Content

- Can a Rotator Cuff Tear Heal Without Surgery?

- Can You Drive After a Rotator Cuff Repair?

- Complete vs. Partial Rotator Cuff Tears

- The Difference Between Rotator Cuff Tears and Shoulder Tendonitis

- Types of Rotator Cuff Tears

- When Not to Have Rotator Cuff Surgery

- Shoulder Pain – Frozen Shoulder

- How to Avoid Shoulder Pain While Playing Golf

- Why Sleeping on Your Side Is Killing Your Shoulder

- Shoulder Pain – Cervical Spine

- The Ultimate Guide for Shoulder Recovery Surgery

- Does a Broken Shoulder Need Surgery?

- How Dr. Craig Miller Uses New Technology to Improve Shoulder Surgery

- Shoulder Arthritis and Shoulder Replacement

- How to Sleep After Shoulder Surgery