Physician Blog by Edward J. Bieber, MD

Shoulder Arthritis and Shoulder Replacement

Shoulder arthritis, although much less common than knee or hip arthritis, has increased markedly in the past few decades with an aging population and increasingly active older population. Generally speaking, shoulder arthritis occurs at an older age than knee or hip arthritis. The shoulder is a ball and socket joint like the hip but with much less bone stock, no inherent stability and the greatest range of motion of any joint in the body. Like other areas of arthritis, the process is the loss of the articular cartilage that covers the joint surfaces and allows for smooth low friction movement between the ball and the socket of the joint. Arthritis can be divided into multiple groups including primary osteoarthritis (the most common type associated with aging), inflammatory arthritis (such as rheumatoid arthritis), rotator cuff arthroplasty (mechanical arthritis caused by the loss or dysfunction of the rotator cuff muscles), osteonecrosis and post-traumatic arthritis. All of these processes lead to a common end stage with the loss of the articular cartilage, increasing pain, decreasing range of motion and eventually deformity and loss of bone.

Many patients can be treated non-surgically. The modalities used include gentle physical therapy, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), topical treatments such as lidocaine patches, and corticosteroid injections. All of these have a role in treatment and have provided varying levels of success albeit in most cases temporarily. Some patients will be able to remain functional with these treatments administered periodically indefinitely. Although there has been a great deal of discussion recently about the use of viscosupplementation (hyaluronic acid), platelet rich plasma and stem cell treatments, there is at this time very little scientific data to support their use.

For patients with unremitting pain not relieved by the above treatments, loss of sleep due to pain, inability to perform activities or increasing bone loss to the point that surgical options would be compromised, there is the option of shoulder replacement surgery. As in other joint replacement surgeries, some bone is removed from the shoulder joint and components made of metal and high-density polyethylene are inserted. The shoulder is unique from other joint replacements because of its much greater range of motion, flat unconstrained glenoid (shoulder socket) and dependence on soft tissues (muscle, tendon and ligaments) for proper functioning and stability. There are some situations when a shoulder replacement is contraindicated and this includes, infection, nerve damage around the shoulder, insufficient bone stock or loss of deltoid muscle function.

The preoperative planning involves appropriate x-rays of the shoulder in at least 2 planes to allow the determination of any loss of bone stock, orientation of the joint and presence of any bone abnormalities. At times, additional studies such as CAT scans and MRI scans are utilized to determine any damage to the rotator cuff tendons or other soft tissues and to further delineate bone damage. Routinely, computer sizing of the appropriate components are determined in advance of all procedures. For patients with significant deformity or bone loss, custom designed devices for determining the proper orientation of the components can be made and at times actual custom cad/cam (computer assisted design/computer assisted manufacturing) components are made specifically for the individual to fit their unique anatomy. All of these high-tech features are available and used when needed but there is no evidence to support their use in routine shoulder replacement cases.

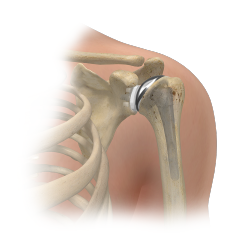

The traditional shoulder replacement is the anatomic shoulder replacement. It involves a metal ball replacement for the humerus (upper arm bone) and an all polyethylene glenoid (shoulder socket, part of the scapula or wing bone). At this time, the glenoid component requires the use of bone cement (methyl methacrylate) for fixation and the humeral component ball may use bone cement or may use biologic fixation. This is a very non-constrained construct and is very dependent on the functioning of soft tissues (including the rotator cuff muscles and tendons). Because of the lack of constraint, there are sheer stresses on the components which can lead to mechanical loosening over time. There must also be adequate bone stock to hold the components so shoulders with either rotator cuff tears, significant bone loss or deformity would not be candidates for an anatomic shoulder replacement. Successful repair of the subscapularis (one of the 4 rotator cuff tendons) is required for successful functioning of this shoulder design. The 10-year survival rate is 93%. It is very reliable in providing pain relief with a reliable range of motion.

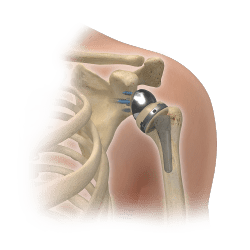

The reverse total shoulder replacement was originally designed 50 years ago and the purpose was to provide an alternative to the anatomic shoulder replacement for patients with deficient rotator cuffs or significant bone loss or deformity. It works by placing the metal ball where the polyethylene socket would normally be attached on the glenoid and placing the socket where the ball would normally be on the arm bone (hence the term reverse total shoulder). This changes the mechanical rotational center of the shoulder which is why it will work with a deficient rotator cuff. This change allows the remaining muscles of the shoulder to pick up the burden of the absent rotator cuff. The design is more constrained than the anatomic shoulder and therefore can accommodate some bone loss and deformity and still function reasonably well but may have slightly less range of motion than the anatomic shoulder. It does not require bone cement and expected longevity is similar to the anatomic shoulder. It is excellent in providing pain relief with a reliable range of motion. It can also be used in older patients with complex shoulder fractures. Because shoulder arthritis occurs at an older age and there is a high incidence of rotator cuff pathology after age 70, the reverse shoulder is quickly becoming the most common type of shoulder replacement.

*Some information excerpted from publications of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons and Orthobullets.

– Edward Bieber, M.D.

Dr. Edward Bieber of OrthoBethesda is the area’s most experienced total shoulder surgeon.

He has been performing anatomic total shoulders since 1986 and reverse total shoulders since 2007. He employs an integrated program of state of the art surgery with the OrthoBethesda physical therapy team to achieve superior results with both types of shoulder replacements. He has extensive experience with computer assisted directional devices and custom made devices for patients with significant bone deformity. Read more here and make an appointment with Dr. Bieber today.

Related Content

- Can a Rotator Cuff Tear Heal Without Surgery?

- Can You Drive After a Rotator Cuff Repair?

- Complete vs. Partial Rotator Cuff Tears

- Rotator Cuff Disorders: The Facts

- The Difference Between Rotator Cuff Tears and Shoulder Tendonitis

- Types of Rotator Cuff Tears

- When Not to Have Rotator Cuff Surgery

- Shoulder Pain – Frozen Shoulder

- How to Avoid Shoulder Pain While Playing Golf

- Why Sleeping on Your Side Is Killing Your Shoulder

- Shoulder Pain – Cervical Spine

- The Ultimate Guide for Shoulder Recovery Surgery

- Does a Broken Shoulder Need Surgery?

- How Dr. Craig Miller Uses New Technology to Improve Shoulder Surgery

- How to Sleep After Shoulder Surgery